Forget the old “eat everything” approach. Here’s how science is rewriting the rules for ultramarathon nutrition.

It’s Not an Eating Contest—It’s a Drinking Contest

Conventional wisdom says that the 100-mile distance is an eating contest with some running. I think that wisdom misses the most critical step.

Modern sweat analyses reveal that 100-milers are a drinking contest. If athletes succeed at the hydration game, they advance to the big boss mode: carbohydrate intake across many hours. But it all starts with hydration.

I noticed something curious when I started coaching pro ultrarunners and doing sweat testing. The outlier athletes who won some of the biggest races in the world often had astonishingly low sweat rates.

Around that time, advice like “drink to thirst” was all the rage. In retrospect, I think we had a problem of availability bias. The champions were drinking relatively small amounts of fluid “to thirst” and succeeding, with that advice percolating to everyone. And most athletes who impersonated the champions were imploding from dehydration.

My Wake-Up Call: When Dehydration Derailed My Dreams

I was one of those athletes.

I raced my first 50k in 2014, and it was nearly impossible. The feeling was so daunting that I didn’t move up in distance until 2023! Thankfully, science came to the rescue.

The Numbers Don’t Lie: My Sweat Test Reality Check

Using a few different methods of sweat testing (primarily at-home tests for sweat rate and the Nix biosensor for calibration), I learned that I am an outlier, too, in the less fun direction. My sweat rate was astronomical, among the highest I had ever seen, and I also had a 95th percentile sodium loss rate.

Even knowing that, the logistical challenge of hydration flummoxed me at the 2023 Canyons 100k, my first longer ultra. I got undersalted and parched on a steep climb. My body stopped taking in calories, and my insides ended up on the side of the trail as I walked to the finish.

At that point, I realized hydration was the gateway to high-carbohydrate diets. Blood volume and electrolyte balance are crucial in transporting glucose to working muscles. I needed serious logistical planning and GI training for my next big race.

Your Hydration Blueprint: Finding The Sweet Spot

Thus, the first step in your 100-mile fueling plan is understanding your sweat quantity and sodium concentration.

Unfortunately, no quantification method gives exact guidelines. Conditions change, and sweat rate changes daily and hour-to-hour (and can fundamentally shift with heat training). The body also has evolutionary mechanisms to modulate sweat levels during long activities.

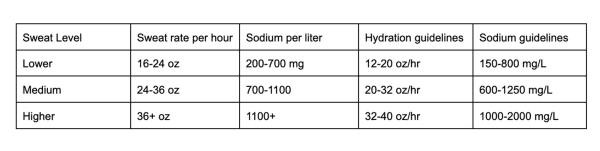

I group athletes into different cohorts for low, medium, and high sweat rate and sodium loss. The difficulty of the hydration equation is that athletes vary wildly in these parameters without any outside indication of why (unlike carbohydrate needs, which are much more predictable).

The Sweat Rate Spectrum: Where Do You Fit?

When I started coaching, the elite ultrarunners I saw might have 0.5 L/hr sweat rates with 250 mg sodium lost per liter. Based on tests, I often lose 1.5-2 L/hr and 1500 mg sodium per liter. Everyone is different, but here is a general way to start thinking about it.

Important note: always work with an expert nutritionist and/or doctor when possible. Use these numbers only as a starting point and calibrate by how you feel with experimentation over time.

Dehydration (hypernatremia) and overhydration (hyponatremia) are both dangerous, with risks that include death if you override body signals. Please be safe!

Fine-Tuning Your Formula

Some notes:

Given how the body stores and burns glycogen, variable effort levels/conditions, and tolerance to slight dehydration, you likely don’t need to replace all your sweat losses. In addition, sweat rates can change massively over time.

For sodium, aim to be relatively close to your losses per liter, with the median level around 950 mg per liter (a solid place to start before you learn what works best for you). Sodium loss likely changes substantially over time, but not everyone agrees.

When athletes are very heavy sweaters, well over 1 L/hr, I suggest they start experimenting with 1 L/hr. This often ends up being plenty even for athletes with higher sweat rates.

All of these numbers are only places to start experimentation in training. You need to practice and train your approach like you train your legs!

My Personal Hydration Strategy

In 100-milers, I aim for 1 L/hr, with a half scoop of Skratch hydration mix and a Precision 1000 tab (500 mg sodium) in each 0.5 L bottle. In cold races, I’ll often be around 0.75 L/hr. It was 100 degrees F (38 degrees C) at the Javelina 100 Mile, and I went as high as 1.75 L/hr (beyond anything I have seen).

I strongly recommend GI training if you will be consuming high levels of fluids on race day.

Level Up: Mastering the Carbohydrate Game

Once you have a flexible hydration plan for your specific needs, it’s time to face the big boss: carbs.

Historically, those same performance outliers of the past often got by on 30-60 grams of carbs per hour, from a mix of sports drinks, gels, and “real food” approaches.

However, the fueling revolution has totally changed the game from a performance perspective. Athletes push harder and nudge their burn rates higher, with carbs lighting the fire.

We don’t need to be better than past athletes. We just need to fuel better so we can push harder for longer.

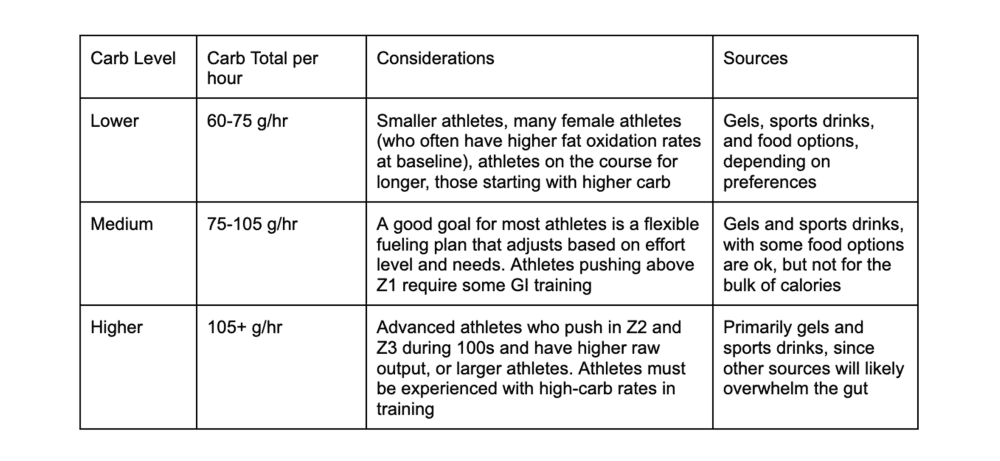

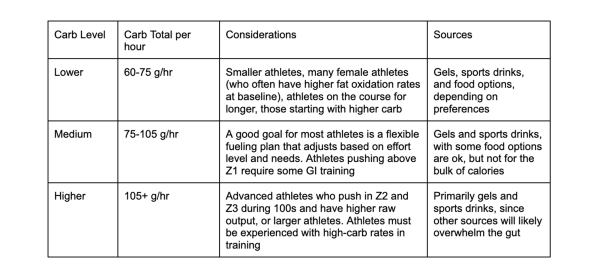

Your Carb Strategy: One Size Doesn’t Fit All

Everyone is different. Athletes who are going faster are on the course for less time. They may be able to push higher carb totals without overwhelming oxidation rates. Athletes taking 30-40 hours for 100 miles likely want to be on the lower end of the spectrum.

Generally, I think the cohort approach is a good place to start.

Why I Ditched “Real Food” for Gels and Sports Drinks

Conventional wisdom says that athletes need 100-mile fueling plans focused on food sources. But based on coaching and personal experience, I don’t think that’s true.

I only use gels and sports drinks to get 140-160 g/hr during 100s (which I don’t suggest anyone try yet, since I’m likely a GI outlier in the same way that athletes of the previous generation were often sweat outliers).

There is mixed evidence on the need for protein and amino acids during the 100s. It doesn’t hurt to have a few grams of protein here and there throughout the day, but it doesn’t need to be a focus of the fueling plan. Also, avoid high doses of fat unless the effort level is very low, given the difficulty of digesting it above Z1 effort.

Training Your Gut: The Most Overlooked Muscle

Let’s bring it all together with some simple math. Excuse me while I get out my calculator and punch in some numbers. OH MY GOSH, THAT’S A LOT OF CRAP IN YOUR STOMACH.

That realization also points out what sets 100-mile fueling apart. Stomach training must be prioritized as a trainable intervention, like training for your legs.

The Three-Step GI Training Protocol

I have a three-pronged approach:

Step One: Practice Race-Day Fueling On your quality long runs, consume fluids and carbohydrates like you would on race day. This will also improve recovery and adaptation rates and allow you to modify your plan based on how you feel. Let your feelings guide you since they incorporate hundreds of physiological variables we aren’t measuring!

Step Two: Push Your Limits in Training During more challenging long runs, experiment with more carbs than you consume on race day. For example, if you aim for 75 grams an hour during your race, aim for 90-105 grams during a moderate 20-miler.

I like to practice the “slurp” method, where I take a liquid gel like Science in Sport Beta Fuel past my palate to prevent flavor rejection on race day.

Step Three: Master the Fluid Bomb Consider building up over time to take in your hourly fluid needs all at once (if fluids are necessary), with proper electrolytes to avoid overhydration.

For example, instead of sipping your bottles over an hour, at the one-hour mark of a 90-minute run, when you need fluids, work toward consuming most of your hourly needs all at once. Then continue running.

Studies have shown that GI tolerance is trainable. This echoes some principles from competitive eater training (they use fluids to prevent the gut “bloat” and involuntary rejection that comes with it).

Just be extremely careful with any GI training, and start with half of your hourly needs only after consulting a health professional.

The Revolution Is Real: Why This Changes Everything

There is still a lot of conventional wisdom floating around the internet.

If you’re undertaking your first 100, you’ll probably be bombarded with 2010 guidance: “Eat quesadillas at every aid station, hydrate with water when you feel like it, sit down in chairs and have watermelon,” and all the rest. I think this conventional wisdom is slower and arguably unhealthy for most athletes.

Through personal experience, I learned that what I thought was an endurance limitation for all those years was a hydration and fueling limitation. Because this realization is happening all at once across the sport, we’re seeing that we’re nowhere close to the limits of what humans can do in ultra events.